(Dante Edition) Space vs. Place, Ambition, Descent and Ascent

2021 marks 700 years since the death of Dante Alighieri, perhaps the greatest poet to ever live.

(T.S. Elliot is supposed to have quipped, “Dante and Shakespeare divide the world between them. There is no third.”)

In honor of the medieval Florentine master, Italy has declared this to be the Year of Dante. This week’s On the Exam? is dedicated to Dantean themes.

Office Hours

Space vs. Place

“How does the Sun know the Moon?”

The question came from the car seat in the back of the minivan.

“Well …” I said, temporarily relieved from my wayward mind’s casting ahead in anticipation of the day.

“Well … the Sun and the Moon are … Brother and Sister,” I said with a smile.

(You would smile too, if you found yourself suddenly engaged in astronomical-poetic discourse with a pre-schooler. Such a development is always welcome, but especially when the alternative is listening to Baby Shark for the thousandth time).

“And where does the Sun sleep?” my daughter continued. “Where does the Moon sleep?”

“Let’s see … the Sun sleeps at night. The Moon sleeps at day. And they both sleep among the stars. I guess you could say they sleep in the heavens,” I said.

“NO. Not the heavens,” she replied imperiously.

“They sleep IN SPACE, Dad.”

One trembles at the prospect of crossing a 4 year-old, not to mention one so confident in her cosmology. I quietly conceded the point.

Later on I got to thinking about that little word: space.

Consider for a moment how much—or, more to the point, how little—is communicated in that most modern of words, space.

Consider that, on those rare occasions when we happen to raise our eyes skyward, what we see before us is not what the vast majority of the human family has seen throughout history.

We do not see the super-abundant, saturated, breath-taking, awe-inspiring, fiery fullness of the heavens.

No. We see … emptiness. Lack. Void.

Space.

What once was a palpable presence has now become a silent absence.

Blaise Pascal, who stood on the cusp of this modern voiding of the heavens, captured the situation of modernity in a sentence that all but trembles with an existential shudder:

“The eternal silence of these infinite spaces fills me with dread.”

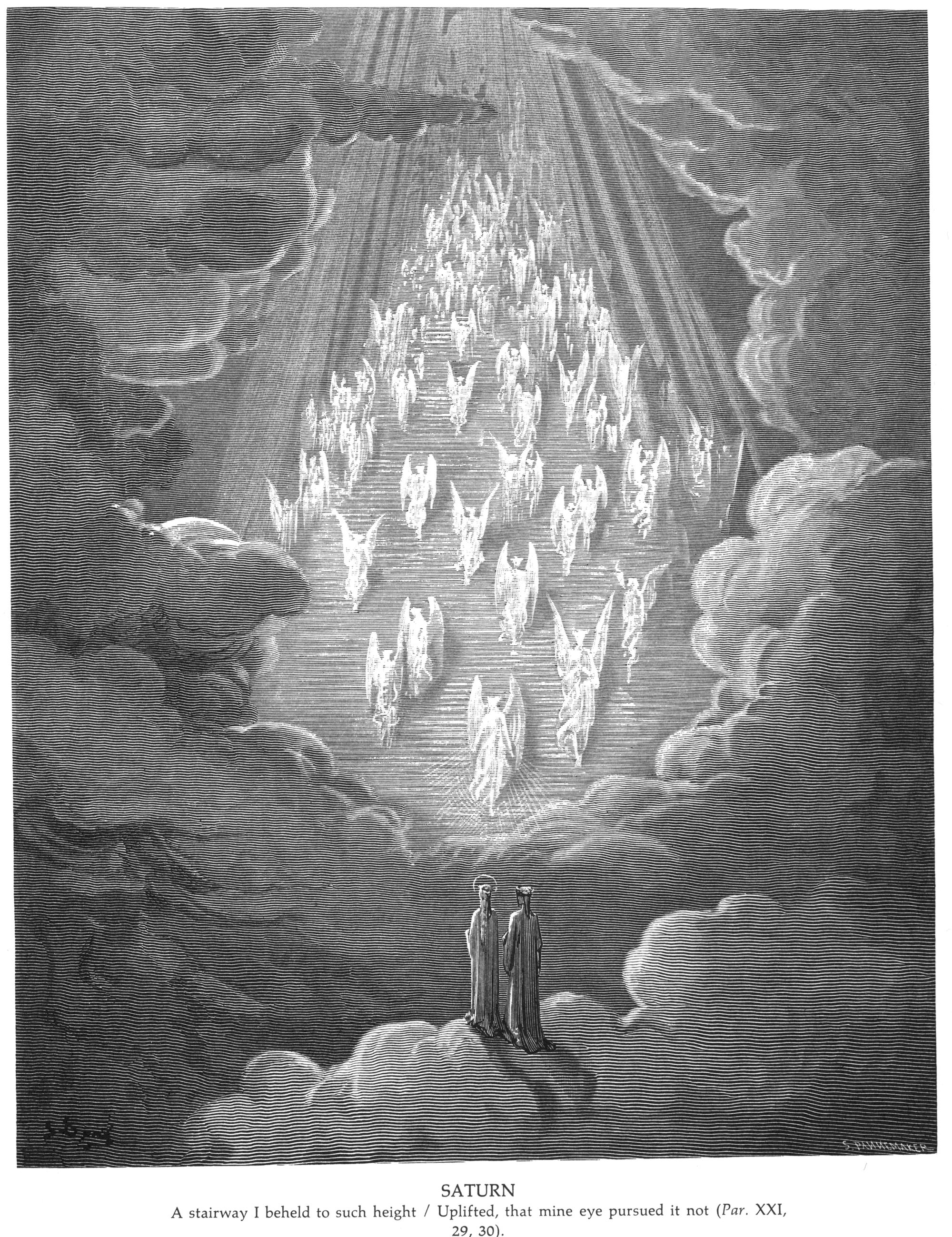

Contrast that with the final verse of Dante’s Divine Comedy, in which the poet sings of

The Love that moves the sun and all the other stars.

Famously, in Dante’s Comedy, the very geography of the afterlife—the yawning pit and tightening circles of hell, the steep slope up mount purgatory, the ever-widening spheres of heaven—the very geography is saturated with spiritual significance. Where you are reveals something about who you are: if you are a flatterer (slinging all sorts of B.S.), then it is no surprise you will find yourself up to your neck in a river of excrement; if you are a penitent learning to curb your anger, then you will be found traversing a terrace in Purgatory, purging your sin by groping through a blinding cloud of smoke, one that reminds you of the rage that blinded you in this life.

Though Dante expresses it with a prodigious and singular imagination, nevertheless in his poetry he is merely giving voice to an assumption that he shared with nearly all those who came before him: the world is not a neutral and empty space, standing inert and submissive to our human projects.

It is, instead, a place, one that surprises and astonishes at every turn.

The difference between space and place is absolutely crucial.

Space is an absence.

Place is a presence.

Space is meaningless.

Place is significant.

Space is empty, it is a lack. It is defined by its nothingness.

A place is full. It is charged. It welcomes or repulses, it envelops, it has proportions. Even when there is no living thing there, a place remains an enabling possibility.

A space is a box with nothing inside.

A place is a stage, the energizing field of drama.

One reason to read Dante’s Divine Comedy today is because the poem can teach us how to view the whole cosmos as a place: saturated with significance, challenging to our presumptions, charged with the drama of existence.

Space is … just space.

Nothing there to see.

The heavens are a place.

We can look up at them with wonder.

Recommended Reading

Ambition

Halfway along in reading a new life

Of Dante, I’m still marveling at the man’s

Conviction he’s been set apart for greatness,

Though of its form

He’s still unsure. So far, in fact, he’s marred

Most that he’s tried and left the rest unfinished,

Promising nonetheless some lasting work

Not yet begun.

I bend still closer to the page, my mind

Halting before a pride it can’t quite fathom.

So it was with the climbing Dante, stopped,

Hunched down, to speak

With the famed illustrator he found crawling

Beneath a marble table on the route

To purification. How he lingered there,

Seeing his future.

He knew the punishment that he would suffer,

And suffer the more harshly for a vice

That strengthened him in flinty solitude

And humiliation.

However true it may be that his poem

Would never have been written had he not

Sealed off his soul from all discouragements,

It was still a failing.

After all, we can see the difference

Between the soldier of true courage and

The one whose brazen recklessness would lead

Men to their deaths.

The woman whom we think a connoisseur

We soon enough will figure out just ooo’s

At everything which sounds like foreign chocolate

Or cellared wine.

But there’s a reason that Aquinas said

That all ambition is a sin. We can’t,

When stiffened by that certitude it brings,

See the cause clear.

For, in the genius plotting intricate rhymes

To execrate the avarice and envy

Of those who burned his home and cast him out

In wooded darkness,

Who passed a sentence on his children’s heads,

And in the gangly dancer without rhythm,

The politician with a taste for fame,

It’s all the same.

It’s terrible that way, like power and beauty.

The mind can hover over its abyss,

Can hear the cataract roaring from below,

And see its force

Shaping the rough stone of the world about us.

But there’s no prior assurance; just the late

Judgment, once we’re past change and bowed to read

Our life’s spread book.

“Ambition”, by James Matthew Wilson

The Hudson Review, 2018

Cultural Event

Descent and Ascent

Friend of the newsletter Matt Chominski runs The Curious Catholic Podcast, a show dedicated to “the personalities, ideas, and movements that have shaped and embodied the dynamism of the Catholic vision.”

I had the occasion to discuss Augustine’s Confessions in relation to Terrence Malick’s film The Tree of Life on Episode 8 of the first season of the podcast.

My own humble appearance aside, that season includes many excellent interviews. (Not to be missed: Erika Kidd on Love and Loss; “Wonder and Wrath” with poet A. M. Juster. But really the whole back-catalogue is worth a listen).

For Season 2, Matt asked me to join him for a nine-part series, keyed to the Roman Catholic liturgical seasons of Lent and Easter, journeying through Dante’s Divine Comedy.

Together we follow Dante as he descends into Hell, ascends up Mount Purgatory, and ultimately journeys through the Heavenly Spheres.

Two episodes are out so far, with new episodes in the series dropping every Wednesday.

The conversation is geared toward first-time readers of the Commedia. So even if you have yet to pick up Dante’s masterpiece, I think you’ll find something engaging and worthwhile in the episodes.

May it be an invitation to partake—during this, the Year of Dante—in the great poet’s stunning vision of this world and the next.

Will This Be on the Exam? Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.