Singing Cicadas, Hummingbird Hearts, Macbeth Masterclass

Office Hours

Singing Cicadas

There's this little spot just outside town.

You head out straight from the city wall, taking the first country path you find. Make a left when you reach a gently curving stream. If you happen to be barefoot, you can easily wade along for a while.

Actually, go ahead and slip off your sandals. Step in. You won't regret it. The water is clear and cool and especially delightful on a summer's day like today.

Just around the first curve you'll happen upon a lovely tree: large branching trunk, wide horizontal branches, broad leaves. It's the kind we often transport to our village squares, but here you find it in its rightful home, drinking deeply from the stream.

There's some shade, a little breeze, and grass to sit down on. You could even lie down if you want. I wouldn't mind a bit. The grass is lush and there's a slope perfect for resting your head.

And the air—it's fresh out here. Go ahead, breathe it in. The tree is in full flower, the petals blossom with perfume.

With your head by the trunk and your feet in the stream, the cares of daily life in the city seem far away. You could do nothing here all day, and be happy.

No to-do list.

No inbox.

Actually, this would be the perfect spot to do something just for you, to enjoy some little pleasure. Not something useful, no business, but something consonant with the loveliness of the place: a little picnic, maybe, or a book of poetry.

Maybe a conversation with a good friend.

Socrates and the young Phaedrus found themselves in just such a spot one afternoon in the 5th century BC. Plato wrote it all down in a dialogue called (conveniently enough) the Phaedrus. The dialogue is a meandering discussion about love, beauty, truth, language, and writing, and it is most definitely worth a read.

But I want to return us, for just a moment, to that idyllic spot under the plane tree.

There's one thing I haven't mentioned yet. Do you hear that sound? It's easy to miss, precisely because it is so present, forming the permanent background hum to Socrates as he speaks, weaving a beautiful myth about the soul's flight into the heavens.

It's the shrill, summery music of the cicada choir.

There's a story, you know, about the cicadas. You've never heard it? A lover of beauty such as yourself should really know this story!

Here, I'll let Socrates tell it:

Once upon a time the cicadas were human beings—and they lived before there were any of those gods of music. When the Muses came into the world, and music made its appearance, some of the people of those days were so thrilled with this new pleasure that they went on singing and singing and singing, and they quite forgot to eat and drink. Actually, they died, and they didn't even notice it. And that's how the race of cicadas came about, because the Muses turned these self-forgetful humans into little creatures with a special gift: they need no sustenance at all, but right from their birth they start singing, they go on singing until the day of their death. And when they die, the cicadas go and report to the gods who among the human beings they saw honoring the Muses with song and dance and poetry. But they also sing to the divine Muses of those who spend their lives devoted to philosophy, for whom the thought and music of heaven are the sweetest of all.

I wouldn't dream of analyzing this moving story of the singing cicadas, lest I dispel its charm and its strange and enigmatic power.

I'll just leave you with this thought: this is an image of a kind of "too muchness", an excess of beauty, which puts us in mind of something—a gift from the gods, a divine overflow—that is more, so much more, than our daily business and utility.

The cicadas seem to look down on us and to beckon, to invite us, to nourish ourselves on a gift that transcends our usual strivings. There is an invitation here to allow ourselves to be carried into the space of the sacred, into that which comes to us as gift.

Our work, our conversation, our lives, take place within the more encompassing song of the cicadas.

(I've adapted Socrates' telling of the myth of the cicadas from the R. Hackforth's translation of the Phaedrus found in The Collected Dialogues of Plato. William Desmond first called my attention to the song of the cicadas. See his book The Intimate Universal (2016), p. 314-15.)

Recommended Reading

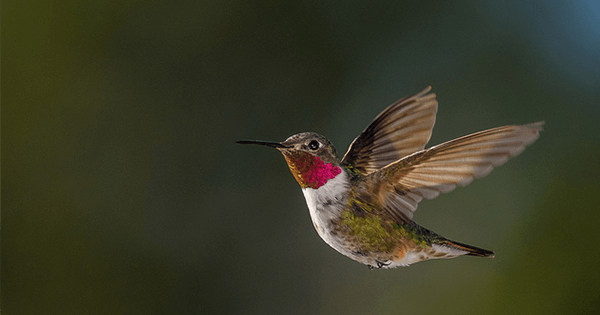

Hummingbird Hearts

Consider the hummingbird for a long moment. A hummingbird’s heart beats ten times a second. A hummingbird’s heart is the size of a pencil eraser. A hummingbird’s heart is a lot of the hummingbird. Joyas voladoras, flying jewels, the first white explorers in the Americas called them, and the white men had never seen such creatures, for hummingbirds came into the world only in the Americas, nowhere else in the universe, more than three hundred species of them whirring and zooming and nectaring in hummer time zones nine times removed from ours, their hearts hammering faster than we could clearly hear if we pressed our elephantine ears to their infinitesimal chests.

So begins Brian Doyle's jewel of an essay entitled "Joyas Voladoras". The whole thing is only six paragraphs long, a model of restraint and wonder, the short essay in almost perfect form.

Do yourself a favor and read the whole thing right now.

And if you want more Doyle, check out the greatest nature essay ever.

Cultural Event

Macbeth Masterclass

Even if you haven't thought about Shakespeare's Macbeth since high school, you no doubt remember the darkly despairing monologue that Macbeth delivers in Act 5, Scene 5:

Tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow

Creeps in this petty pace from day to day

To the last syllable of recorded time,

And all our yesterdays have lighted fools

The way to dusty death. Out, out brief candle!

Life's but a walking shadow, a poor player

That struts and frets his hour upon the stage

And then is heard no more. It is a tale

Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury,

Signifying nothing.

On the Exam? reader Gabe pointed me to this short archival clip of the unparalleled Ian McKellen walking us through those lines and showing how Shakespeare's language is so effective in communicating to the actor how he is to embody the verse.

Does it get much better than Gandalf explaining Shakespeare?

Will This Be on the Exam? Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.